| Urological Oncology urologic malignancies, including prostate, bladder, kidney, and testicular cancers |

|

| NeuroUrology interventions for the vast array of neuromuscular pelvic disorders |

|

| Robotics minimal invasive, 3D, tactile experience, for what was previously maximally invasive urologic surgery |

Urological Oncology ... Prostate Cancer Prostate Cancer In General……… Prostate cancer is one of the most common medical conditions seen by physicians in the United States. Not surprisingly, it is the second most common type of cancer diagnosed among men in this country. Only skin cancer is more common.

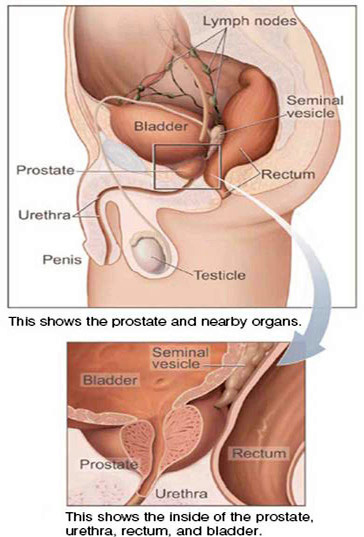

The prostate is an important part of a male’s reproductive system. It is a glandular organ located in front of the rectum and underneath the bladder. The prostate surrounds the urethra, which is the tube that carries urine from the bladder through the penis to the outside world. A normal prostate is about the size of a walnut. However, if the prostate gland grows too large, it may compress the urethra, which could slow or even stop the flow of urine from the bladder through the penis. The prostate is a gland that makes the alkaline (non acidic) portion of seminal fluid. During ejaculation, the seminal fluid helps carry sperm out of the man's body as part of semen. Male hormones, technically known as androgens are the biochemicals that make the prostate grow. The testicles are the main source of male hormone production. Although there are many different subtypes of male hormones, the most predominant subtype is known as testosterone. The adrenal gland also makes testosterone, but in small amounts.

Cancer Cells Cells are the building blocks of all living things. When groups of like cells grow together, they make up sheets known as tissues. Tissues make up the organs of the body. Normal cells grow and divide to form new cells as the body needs them. When normal cells grow old or get damaged, they die, but the body knows to make just enough new cells to take their place. The membranes of our cells contain sensors that stop the growth of that cell. However, sometimes, this process goes wrong. Sensors in the cell membrane don’t tell the cell to stop dividing and making new cells. Consequently, new cells continue to form even when the body doesn't need them. The buildup of extra cells form a lump of tissue which then becomes a mass of tissue that is commonly known as a tumor. Prostate tumors can be benign (not cancerous) or malignant (cancerous). Cancer cells can spread by breaking away from the prostate tumor. They enter blood vessels or lymphatic vessels, which branch into all the tissues of the body. The cancer cells can attach to other tissues and grow to form new tumors that may damage those tissues. The spread of cancer is called metastasis. Normal (Non Cancer) Cells Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH) is a benign growth of prostate cells. It is NOT cancer. The prostate grows larger and squeezes the urethra. This prevents the normal flow of urine. BPH is a very common problem. In the United States, most men over the age of 50 have symptoms of BPH. For some men, the symptoms may be severe enough to need treatment. Risk Factors When you're told you have prostate cancer, it's natural to wonder what may have caused the disease. But no one knows the exact causes of prostate cancer. Doctors seldom know why one man develops prostate cancer and another doesn't. However, research has shown that men with certain RISK FACTORS are more likely than others to develop prostate cancer. A risk factor is something that may increase the chance of getting a disease. Who Should Be Screened for Prostate Cancer? If William Shakespeare lived in the Age of Prostate Cancer, he may have asked “To screen or not to screen” that is the question. However, the answer of whether or not to screen is a personal and complex one. It’s important for each man to talk with his doctor about whether prostate cancer screening is right for him.

|